for East Timor work

Indonesia boycotts ceremony

December 10, 1996

OSLO, Norway (CNN) -- An outspoken bishop and an exiled activist accepted the Nobel Peace Prize Tuesday for their efforts to bring a peaceful end to a two-decade long conflict with Indonesia in their native East Timor.

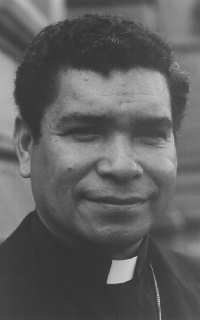

Roman Catholic Bishop Carlos Filipe Ximenes Belo accepted his share of the $1.2 million prize in the name of the church and the "voiceless people" of East Timor.

"What the people want is peace,

an end to violence and the respect for their human rights," Belo said.

"It is my fervent hope that the 1996 Nobel Prize for peace will advance

these goals."

Both Belo and activist Jose Ramos Horta, who

now lives in Australia, called for talks with Indonesia. Ramos Horta said

that a committed effort from all sides would be needed to succeed in bringing

peace to East Timor.

"Our society will not be based on revenge," he said. "Because of its credibility and standing, the Catholic Church will be expected to play a major role in the healing process."

Catholic Bishop Ximenes Belo

Vice President of the CNRT, Ramos Horta

Indonesia was incensed over Ramos Horta's selection, and refused to attend either a reception with Norwegian royalty or the Nobel ceremony itself, held on the 100th anniversary of the death of Swedish dynamite inventor Alfred Nobel, the prize's benefactor.

Indonesia accuses the self-exiled East Timorese of inciting unrest in East Timor, which it has occupied since Portugal abandoned it in 1975 during a civil war. Since that time, Indonesia has been accused of gross human rights violations while battling the East Timorese independence movement.

Indonesia annexed East Timor, but the United Nations has never recognized the annexation, and still considers Portugal the administrator of East Timor.

The Indonesians also reportedly warned Belo to temper his remarks or face possible exile or other repercussions when he returns home. A spokesman for the Indonesian government denied the suggestion.

The Indonesian government did

criticize Belo after his selection for the prize, however, for allegedly

telling the German magazine Der Spiegel that Indonesian troops treated

East Timorese as "scabby dogs" and "slaves." Belo said he was misquoted.

Man of the cloth, man of politics

The two Peace Prize winners approach efforts to bring peace to the conflicted territory differently. Belo, the fiery clergyman, has been called upon by the Indonesian government to mediate disputes, and has cautioned East Timorese youth to cease their own violence against the Indonesian occupation.

The bishop said Tuesday that he was reminded of 1964 Peace Prize winner Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. "standing on the mountain top, looking out at the promised land." Those words, he said, reminded him of the mountains of East Timor.

Seeing those mountains, he said, "I feel ever more strongly that it is high time that the guns are silenced in East Timor once and forever."

Horta, who fled East Timor three days before the Indonesian invasion, has long advocated independence. Portuguese authorities exiled him from 1970 to 1972 for his activities, and he now campaigns around the world for independence. An independent East Timor, he said, would have no standing army, and would build a "strong democratic state."

"East Timor is at the crossroads of three major

cultures, (Melanesian, Malay-Polynesian and Latin Catholic)," he said.

"This rich historical and cultural existence places us in a unique position

to build bridges of dialogue and cooperation between the peoples of the

region."

(From CNN and Reuters)