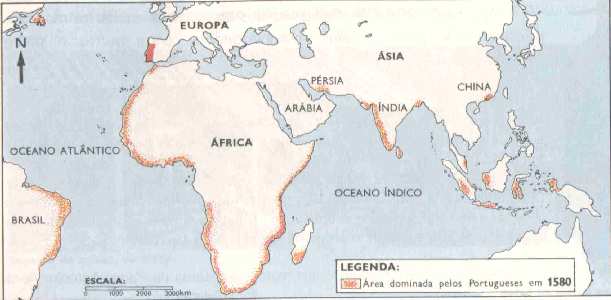

Portuguese colonial empire

Up to the final

years of dictatorship in Portugal, in spite of the condemnation of UN and

the start of the guerrilla warfare in the African colonies of Angola, Guinea

and Mozambique, the Portuguese Colonial Empire was defended by the government

as an heritage of the glorious past and motive of national pride. However,

the crescent expenses of it's maintenance begun to reflect increasingly

on the economy and social tissue of the metropolis, what provoked crescent

discontentment of the population, finally leading to the Revolution of'

1974 that installed democracy and gave independence to the colonies. East

Timor was invaded by Indonesia precisely in the course of decolonisation.

The meaning of the Portuguese Colonial Empire

During dictatorship, the colonies continued to be dedicated considerable interest. For the nationalist ideology that characterised the regime, the vast regions of the World under Portuguese sovereignty were to be seen as the justification of a necessary conscience of greatness and pride to be Portuguese.

The expression "Portuguese Colonial Empire" would be generalised and

even met official formalisation. Colonial patrimony was considered as the

remaining spoils of the Portuguese conquests of the glorious period of

expansion.

These notions were mystified but also expressed in Law as in 1930 Oliveira

de Salazar (at the time minister of Finances and, for some time of the

Colonies) published the Colonial Act. It stated some fundamental principles

for the overseas territorial administration and proclaimed that it was

«of the organic essence of the Portuguese nation to possess and colonise

overseas territories and to civilise indigenous populations there comprised».

The overseas dimension of Portugal was however soon put at stake after

World War II. The converging interest of the two victorious superpowers

on there-distribution of World regions productors of raw materials contributed

for an international agreement on the legal right for all peoples to their

own government. Stated as a fundamental principle of the UN Charter, anti-colonialism

gave thrust to the independent movements of the colonies, and in matter

of time unavoidably accepted by the great colonial nations: England, France,

Netherlands, Belgium. Yet such countries relied on mechanisms of economical

domination that would last, assuring that political independence wouldn't

substantially affect the structure of trade relations.

Loss of the Indian territories and the reactions. The first problem

that the Portuguese had to deal with was the conflict with the Indian Union,

independent state in 1947. The Indian nationalism had triumphed over the

English occupation, and in 1956 forced the French to abandon their establishments

in 1956. The same was demanded to the Portuguese over their territories

of Goa, Daman and Diu, but in face of refusal. India severed the diplomatic

relations. The passage through Indian territory in order to reach the two

enclaves dependent of Daman was denied since 1954, and despite the recognition

of such right by International Court of Justice recognised t(1960), Dadrá

and Nagar Haveli were effectively lost. This was followed by mass invasions

of passive resisters which Portuguese were still able to hinder until December

19 of 1961, when the Indian Union made prevail it's superior military force,

to obtain final retreat of the Portuguese.

Goa had been capital of the Portuguese expansion to the East. Conquered

in 1510 by Afonso de Albuquerque, it was also an active centre of religious

diffusion to the point of being called the Rome of the Orient. In spite

of it's the historical and spiritual importance, the reactions against

the military attack of the Indian Union parted mainly from official sectors,

and only moderately shared by the public opinion. For the historian J.

Hermano de Saraiva whom we have followed, it reflected the dominant politic

ideologies: at the end of the XIX th century, the colonising activity was

considered a service rendered to civilisation but since World War II viewed

as an attempt to the liberty of the peoples. This <<doctrinal involucre

of interest to which we [the Portuguese] were completely strange was rapidly

adopted by the intellectual groups, in great part responsible for the formation

of the public opinion>>. That's how Saraiva justifies that the protests

for the loss of Goa to the Indian Union were directed less to the foreign

power than to the Portuguese authorities, <<for not having known

to negotiate a modus viviendi acceptable for both parts>>. More than that,

he detects in this curious reaction a tendency that would accentuate along

the two following decades: the crisis of patriotism. To defend or to exalt

the national values appeared to the bourgeois elites of the 60's as a provincial

attitude, expression of cultural under-development.

The Portuguese colonies and UN International efforts for Portugal to grant independence to it's overseas colonies begun as soon as the country joined UN in 1955. Having denied thepossession of non-autonomous territories, on the base that decolonisation of the overseas territories had occurred through their integration in Portugal. They were declared to be no longer dependencies of the metropolis, but designated <<overseas provinces>> (since the constitutional revision of 1952) benefiting of a unitary constitution. So being, the Portuguese didn't follow the regulations of UN concerning the non-autonomous territories like for instance the duty of the administrative powers to present current reports about them. It was a procedure previously adopted by countries like France, England, Denmark, Netherlands and even USA, which defended the right to decide whether to apply the regulations or not. Anyway Nonetheless, the validity of Portugal's posture would be strongly contested among the nations of the Soviet and Afro-Asian blocs.

The anti-colonial movement reached a high point in 1960. The General

Assembly adopted a resolution sponsored by 43 Afro-Asian countries called

Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples.

It condemned «the subjection of peoples to alien subjugation, domination,

and exploitation», declaring that «immediate steps shall betaken

(...) to transfer all powers» to the peoples in the colonies «any

conditions or reservations, in accordance with their freely expressed will

and desire (...) in order to enable them to enjoy complete independence

and freedom». The resolution was approved by a score of 89 - 0, and

9 abstentions and Portugal was one of the chief targets.

The start of warfare in the African colonies

If until 1961 the offensives against Portugal were reduced to speeches

and motions during the assemblies of the UN, in February of that year outburst

thefirst waves of violence against Portuguese rule, by Angolan guerrillas.

The rest of the History, and essentially what concerns

East Timor, you will read it in other articles of this

magazine.